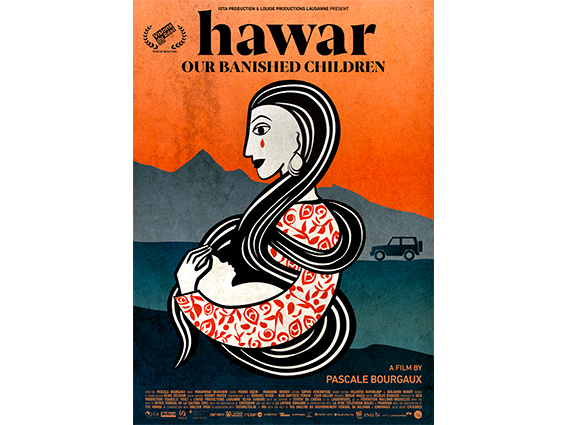

Some documentaries defy a well-composed press release. Hawar, Our Banished Children by Pascale Bourgaux is one such film. In many ways it is an old tale about the fate of children born in a time of war. But these are no ordinary war babies.

In 2014, thousands of Yazidi women were kidnapped by Daesh and reduced to sexual slavery. Upon her release, Ana is forced to abandon her baby following the rapes she suffered. Considered the “bastards of Daesh”, children born of rape by jihadists have been rejected by the Yazidi community. After four years of separation, ‘Ana’ crosses Kurdistan in secret to see her daughter Marya again. She is the first Yazidi mother-survivor to break the omerta.

Andrew Threlfall talks to the director, Pascale Bourgaux about her passion to tell this harrowing story.

AT: There were so many moments that I broke down watching your film, but, I wanted to start by asking if you knew about Anni-frid from ABBA? Her mother had a sexual encounter with a German U-boat captain, and similar, perhaps the only similarity to Ana in your story – is that the local community ostracised her and that’s why she and Anni-frid had to move to Sweden.

PB: I did not know about the Abba singer’s story. There is a big difference with the Yazidi’s drama though: Ana didn’t have any choice. Ana was kidnapped and raped by her enemy. But you are right, there are some similarities: Anni-Frid and her mother were banished from their community. The mother made a clear choice: she choose to stay with her daughter, even if the price was to break with her family. In the case of Ana, she refuses to do this choice. She is still living with her family. She still today maintains a secret relationship with her daughter by phone. The question here is why a victim is confronted with this dilemma? Why does Ana have to choose between maternity or her community? I started this film process in 2014 when Isis invaded Iraq. When I first tried to get somebody to take part, the Yazidi people just kept saying, ‘No, no, we don’t know about these kids’, but it was obvious that if they had been raped en masse in August, then the first babies would be born in April and I kept going back year after year asking where these kids were and nobody would tell me. It made no sense to me that these babies could disappear. I even came across an orphanage in Kurdistan who said, ‘We don’t know about these kids.’ For over five years I could not locate any of these disappeared children.

AT: There is one scene in particular that really stood out. Where Ana is in the car driving a long distance to finally have a reunion with her daughter. Sheep are crossing the road and, well you describe what happens next…

PB: Andrew that scene was completely by chance but Ana actually knows how to deliver sheep in real life. The lamb being born was completely by chance. I didn’t know that she used to take care of this in her own family, delivering sheep. Deprived of her own child but able to help deliver another life, it obviously feels and looks like a metaphor for the whole film. We got there to the roadside and we thought that all the lambs had been born but then Ana said I think there is another one in the belly and she was right, and delivered it.

AT: Marked by contrast the brutality, and I suppose hopelessness of the Yazidi women who in a heartless way say that the children are not welcome.

PB: We met Ana in 2019 and explained to her that we understood how it could be dangerous for her. Ana is so brave. We follow a protocol of security very strictly in order to protect her identity.

AT: I’m fairly sure that if the girl in Hawar is only 19 when she was raped by Isis, she would have been a virgin?

PB: Yes, they all are. The girls were being sold openly on the market. Photographs of them were exchanged on WhatsApp in both Syria and the parts of Iraq controlled by Isis. The Yazidi girls who were kidnapped by Isis were kept in a house and systematically raped. And they’d see the girls as people they can move on and exchange. The virgins were sold for 200 to US$300. There were also women who perhaps had been already married and had kids sold for 50, or as little as $20.

AT: This is such an important and vital piece of work. Will you take it to the documentary festival circuit now?

PB: The first premiere of the film in Visions du Réèl, in Nyon, Switzerland. It was so important for the film and the cause of those Yazidi mothers. It’s important to understand that this film is not against the Yazidi community but on the contrary, we did it to help them to open up a debate. Some part of the community is moderate, there are open minds. Yazidis who try secretly to help the mothers and want to integrate and accept the kids in the community. But the conservative clerical authorities refuse to listen to them and to change. So many mothers and children are suffering because of illegal forced abandonment and illegal adoptions. There was one story we were going to include about one mother who had had two children after being raped and she was obliged to pacify her family and abandon them in Syria but because she loved her children so much she started looking for them even though both children had by then been adopted by a couple who had the dream of having their own child but were unable to. So we met the couple and we filmed them and they were so happy to finally have kids in their life and they had raised them for two years and then one day the mother calls them and says we are very sorry but can you give the children back. Just wow. Then what followed was official pressure from the local Kurdish administration where the raped mother received support to have her children returned. In the end, the adoptive parents said they would agree to give them back if they can just meet the mother. It was heartbreaking. I asked many Yazidi men and women why don’t you just change the way you think and allow these children and women into your community to be loved? But their continual answer was a very racist response that they, the children, had Daesh blood so one day they will grow up to be terrorists and harm us.

AT: What do think was the essence of Ana and her story?

PB: The girl whose story we made is so amazing because she was the sheep keeper captured by Isis, then she was raped, then become a mother against her will and then became attached to her baby and when she is finally free, she is forced to abandon her baby by her family. In secret, with the help of some open-minded Yazidis, Ana found which orphanage her daughter was in. She traveled to the orphanage to see her kid, kiss her, and spend time with her. And also to make the legal process to the Court to be recognized as the mother. Ana’s goal was to avoid the illegal adoption of her daughter. A lot of these children have been given illegally to adoptive parents without the consent of the birth mother and some of these mothers know that there are kids living just two streets away and they cannot do anything because maybe the judges do not want to reopen the case and also of course because a Yazidi family might refuse to support bringing the child back. The second goal of Ana was to take her daughter out of the orphanage, and she found this unbelievable solution: to give the custody to the paternal grand parents…the parents of the jihadist, her rapist!

AT: And these people are the most loving people you can ever meet. They love their grandchild, who is half Yazidi. Amazing?

PB: Ana’s testimony represents all those Yazidi mothers who cry in silence. This film is for a thousand ‘false orphans’ growing up in orphanages when their mothers love them and miss them. This story is universal because, in all wars, be they in Congo, Rwanda, Bosnia and tomorrow in Ukraine, we must learn to integrate the kids born out of the rape from the enemy. It should not be problematic because both the mothers and the children are victims.

We talked to Ukrainian film director, Valentyn Vasyanovych about the difficult emotions that flow through his film set in the war in Ukrain, Reflection. Read about it here