Film Director John Matthews explains how a moment of seemingly trival posativity changed his life and lead him to make a film of the deadlyest crash in the history of motor racing.

June, I can’t remember when it was. 2007? Anyway, it was the second time I was filming in the pits at the Le Mans 24 Hours. The previous year I had made a film called ‘Le Mans – In the Lap of the Gods’ which had became popular with racing fans. I filmed Martin Short, aka ‘Shorty’, a man famous for his short temper who had a ‘bit of a reputation’ according to a journalist I knew. We filmed his frustration struggling to realise his dream of standing on the podium of the greatest race in the world. His heroic attempt, in a car that had never been tested before, was compelling and remains highly entertaining many years on.

On that pit straight I was asked by someone I did not know yet, Clive Stroud [who turned out to be a book dealer who I still do business with to this day]. ‘John can I have a copy of your Le Mans film please?’. ‘Well of course you can, but am not giving it to you, it is how I earn my living. I’ll do you a swap if you like.’. ‘How about this book?’ Clive offered, wafting an ugly tome with a scratchy cover about racing Jaguars at Le Mans. My face said it all.

Instinct, being British, was to immediately retort ‘no thank you’. But having recently been on an Americanised course encouraging me to ‘say YES’, I bit my lip, turned around and said ‘Ok, why not’. I handed over a copy of ‘In the Lap of the Gods’, not in any way wanting a book about old Jaguars, but beginning my journey of ‘The YES Way’.

If I had said no to that book, my life would have been completely different. I have no idea where I would be right now.

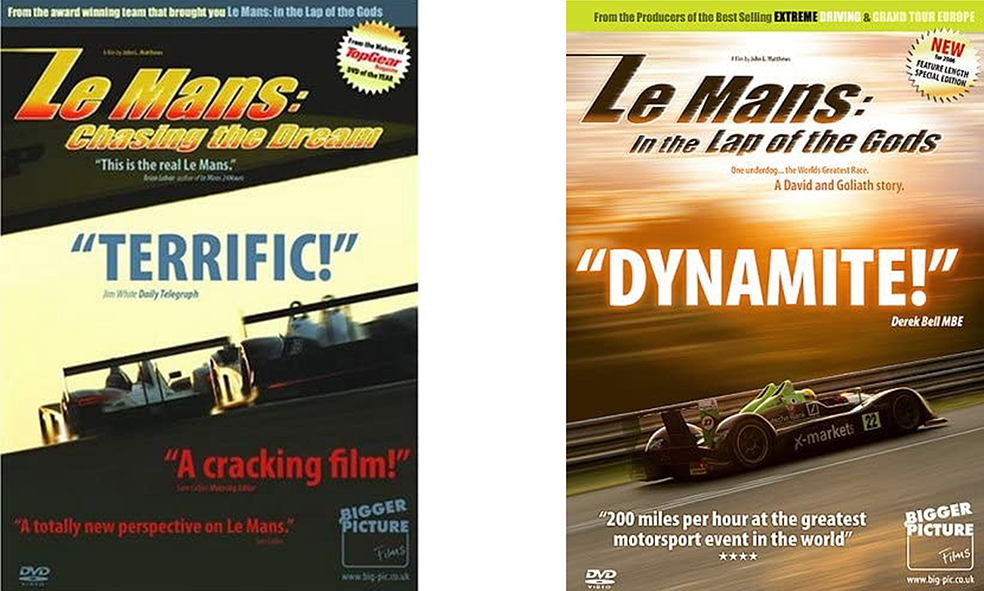

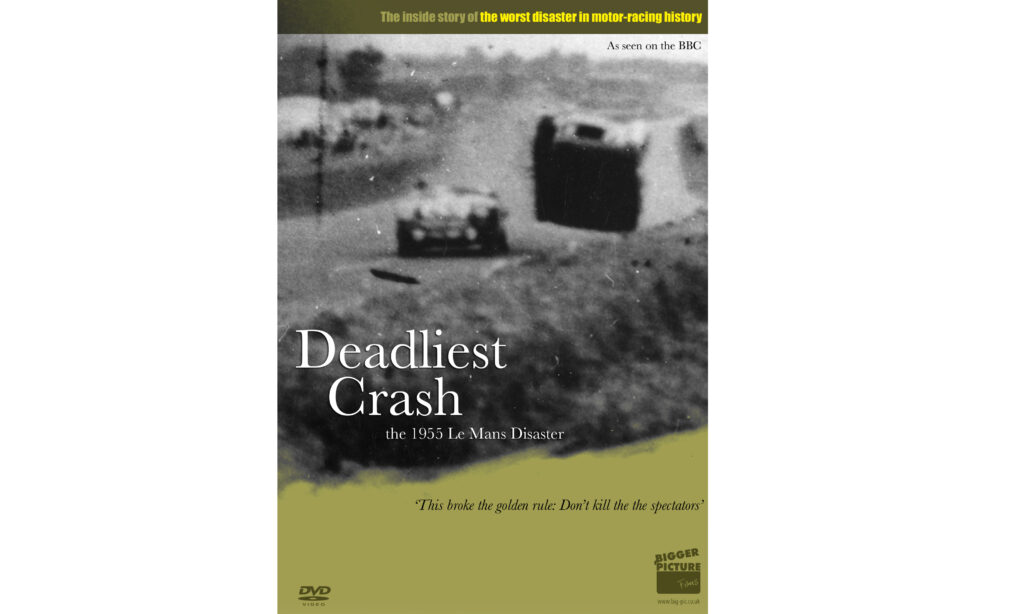

Later, flicking through the book I did not want, I came across a series of photographs, used in a court case to get top racer Mike Hawthorn off from being blamed as the cause of the deaths of 84 people at the 1955 Le Mans 24 Hours. At this tragic race, long forgotten by some, a works Mercedes driven by Pierre Levegh crashed into the crowd, chopping off the heads of dozens of spectators and slicing others completely in two. It left a bloody mess splattered all over the grandstand. The magnesium Mercedes in a fireball that nobody could extinguish, left to burn to ash.

Having been at Le Mans twice before, in a big way, making films in the heart of it all, I wondered how nobody ever mentioned this story? Why had I and no one else ever heard of it? I could not get those images out of my head. The story stayed on my desk for months. And months. And more months.

I did not realise it, but saying ‘yes’ had sent me on a journey that would take up the next three years of my life.

The story of this terrible disaster had to be told, and it had to be done now as it had happened fifty five years ago, the main protagonists, if not already dead, would soon be so. It needed recording, it was an important story and it was one I could not allow to die along with those involved.

With help from a local film initiative, I set off with my then friend and film making buddy Rich Heap to Connecticut, New York State, USA, to interview an affidavit from John Fitch, Mercedes team mate of Frenchman Pierre Levegh, who having also died in the crash, had been blamed for the deaths. ‘The dead can’t sue’ said Chris Hilton, one of our interviewees.

John, who was ninety six at the time [and has since passed away], could remember in vivid detail what had happened that day. He was a key player in what was and remains the biggest motorsport disaster of all time. John and I became friends, he admiring my get-up-and-go to come three thousand miles across the Atlantic with my camera, hire a van, to film a ninety six year old drive a sixty year old racing car around a track. John said to me ‘This will be the biggest disaster in motorsport, until there is a bigger one. History is important John, so we don’t make the same mistakes twice.’ He was glad the story was to be recorded for history. [Affected by the crash and the death of his teammate and friend, Pierre Levegh, John went on to invent many road safety innovations, including the Fitch Safety Barrier, used all over the world to save lives on motorways.]

John was convinced that racing hero Mike Hawthorn was to blame for the crash, but Hawthorn’s teammate Norman Dewis, another healthy eighty odd year old, had other ideas. There was much tension and contradictions, so much so that we built a computer model to try and work out exactly what had happened. This was an important story that involved the biggest racing names of the day such as Fangio, the greatest racing driver that ever lived, and an event that would end Mercedes’ racing ambitions for thirty years.

The race, despite the mass bloodshed, was never stopped. Boy Scouts were given the gruesome task of matching heads to the bodies lined up under the stands. Above crowds filled the gaps in the grandstand left by the dead.

Researching what happened, we met many witnesses from the disaster. Including a lady who had never talked about the crash, not even to her husband. Madame Pasquier told how she had been almost beheaded by pieces of the car, how her husband had thrown her to the ground to save her, how her hands were burnt and how she thought she would never hold her baby again. At the end of the interview, in her kitchen, she tried to hand over some money. She felt that I had given her some kind of service by listening, the only person to do so in almost sixty years, and that that required formal acknowledgement. Of course, I told her that I could not possibly accept any money and that it was not something that she should expect to pay for. It was the most astonishing interview I have ever made.

Nominated for the prestigious Grierson Award for Best History Film

Whilst the race carried on, Mike Hawthorn and his Jaguar team eventually lifting the victory cup, Mercedes pulling out, people like Madame Pasquier and hundreds of others would be left to pick up the pieces for the next sixty years.

For several years after the film was launched people were still coming forward to talk and share their experiences. To this day there is no fitting memorial for those that died and were scarred that day.

After carefully piecing together on film the tragic events of that fateful day at Le Mans in 1955, John went on to give a voice to other overlooked stories in the history of motorsport.

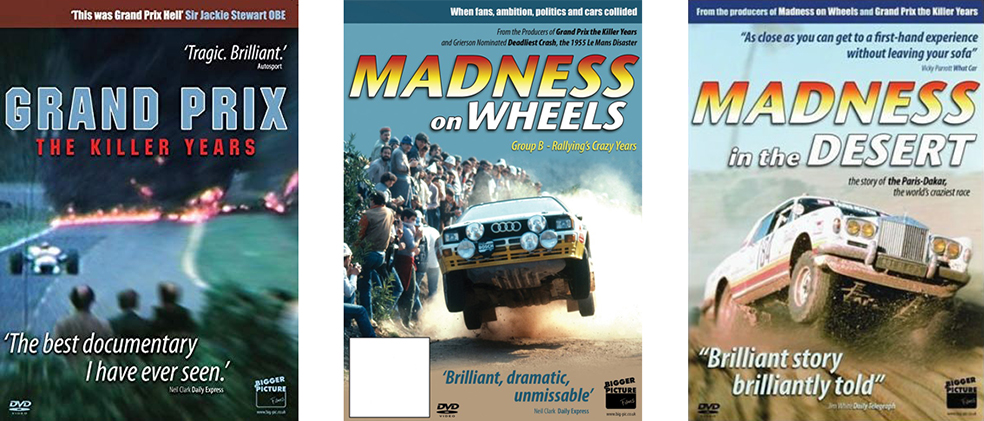

John’s film ‘Grand Prix The Killer Years’ for the BBC, has become famous all over the world. It documents a time in the 1960s and early 70’s when Grand Prix drivers were considered almost expendable. Life and death were just part of the race until the drivers fought the authorities and demanded changes that have followed to this day.

John Matthews also has written books and made many other films, documentaries and feature films. You can find them all at Bigger Picture Studios

In Le Mans, you’re never far from the 24 Hours. Find out our favourite places to visit, eat and stay here